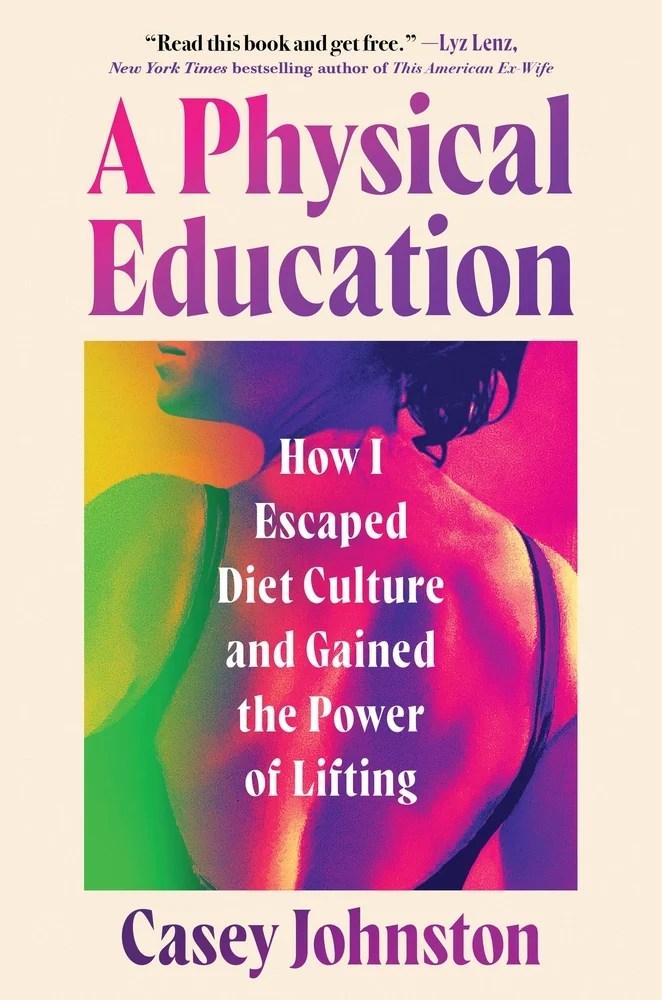

I recently took a break from research work to read Casey Johnston’s new memoir A Physical Education: How I Escaped Diet Culture and Gained the Power of Lifting (Grand Central, 2025). I highly recommend it. I loved a lot about the book, including Johnston’s prose style, her engaging account of her own changing relationship to her body, and her lucid introduction to both the science and history behind weight lifting.

Despite the difference in our situations, much of what Johnston describes as a growing awareness of what her body actually could do, and the pleasure that brings, resonated with me. If there were ever an effective way to alienate a shy, chubby gay kid from his own body, it’d be the diet culture and bullying that I grew up with. My recovery from all that didn’t start with weightlifting but lap swimming, when a friend of mine bought me a year-long membership to a Master’s swim club for my 30th birthday. I’ve felt it again more recently after taking up strength training. What seems like the absolute magic of it all is that even as the desire to look a certain way drove me into swimming (and then lifting), those impossible standards mattered less and less as the sheer pleasure of the activity and the felt transformations they produced became the reason to keep doing it. That’s not an apology for bullying and diet culture, as if they were the motivation I really needed, but just to say that if introduced right, then things like strength training will sell themselves. Johnston’s book also makes a compelling case for them, especially for women and, I’d say, other people who traditionally haven’t been publicly identified as the proper subjects of lifting.

It was also somewhat surreal reading Johnston’s memoir while working through Fit for TV: The Reality of the Biggest Loser on Netflix. I’ve struggled to figure out what that documentary is trying to do, beyond being the next entry in the current stream of exposés about 1990s and early 2000s reality TV. Still, it felt very different from Johnston’s book, and here’s why I think so: Physical exercise, eating, and the ability to take pleasure in one’s own bodily capacities are deeply political things, even as they are lived on a personal level. I appreciated the way that Johnston tries to make these connections explicit by tracing some of the roots of American weight lifting culture into 19th century socialist movements, its subsequent adoption by the cult of Muscular Christianity, and so on. It’s something I wanted more of from Fit for TV: the filmmakers managed to secure an interview with Aubrey Gordon from the Maintenance Phase podcast, whose usually really good on that stuff, but she seems underutilized here. Instead, we largely get something to the effect of: “aren’t the people who ran this show awful?” And, yeah, they kind of are, but the show’s success hinges on the fact that the audience was already primed to receive the message it was propagating. Gordon is there to make that point, but then the more interesting questions, like why and how, go unanswered. The doc doesn’t really try to connect the personal stories to something larger beyond a culturally diffuse and seemingly ahistorical phobia about fat bodies.

You could say that the filmmakers wanted to focus on the personal side of things, and okay, that’s fine. But then what’s the difference between Fit for TV and the reality show itself, whose producers argue that they wanted to show inspiring personal stories of people on weight loss journeys. Fit for TV certainly affords more human dignity to former contestants than the reality show ever did, but, like, it gets a lot of mileage out of rehashing clips from The Biggest Loser, including a lengthy highlight reel of contestants vomiting on camera. Even though we’re supposed to look at those clips and think “gosh, how awful,” they tap into the same voyeuristic pleasure that the original show so successfully capitalized on. I think the doc needed to make those bigger connections, and the easiest way to do it would’ve been via some kind of historicizing.

There are other ways that diet and lifting are political, of course. As a quick example: this report on Palestinian lifters devising ways to keep up their practice in the face of Israel’s restrictions on food deliveries to Gaza and the devastating famine conditions it has created. As much as the lifters are struggling to survive, they recognize the utopian potential in the practice. As Mohamed Solaimane reports: “The tent gym, despite its limitations, serves as what al-Assar calls a challenge to ‘the reality of genocide, destruction, and displacement’.”

Anyway, Johnston’s memoir does a better job than Fit for TV of connecting dots between exercise cultures, their partial origins in 19th century socialist exercise movements, and their complicated contemporary ties to “wellness” and right-wing movements, even though her personal story remains the center of the memoir. Like I said, I recommend the book. Finally, I learned about Johnston’s work not through her writing on diet culture but through an interview she gave on one of my favorite podcasts, Tech Won’t Save Us, where she discussed the tech-fueled attention economy and the process of turning one’s smart phone into a dumb phone. I recommend that, and the podcast, as well.